Knocked Down But Not Out: Plaster, Drywall, and American DIY, by Michael Ward

Planning a child’s nursery is like planning a funeral. Rarely is either undertaken with the express wishes of its guest of honor. The baby is unable to offer its opinion on which paint colors—for example, white gallery, Greek villa, or snowball—better captures the warm light filtered through a neighbor’s dying holly just outside the window. Similarly, Aunt Nancy is unable to opine on the tulip arrangement that graces her coffin even though she hated tulips and told everyone every chance she got. We arrive to this world in tyranny and depart from it likewise.

As I write this, my wife and I are behind schedule preparing our daughter’s nursery. This is a room composed of four walls built out of two-by-fours and drywall nailed together by a group of workers around the very same year that I was born. I remember nothing about my nursery. My daughter, who is due in about three months, will likely remember nothing of hers. But my wife and I have spent hours mulling over the finer points of paint, light, and the impossibly quaint scam that is a changing table. We are working so hard on this room because we will remember the time we spent in it and what it meant to us as first-time parents. In that way, it is our room as much as our daughter’s.

The nursery’s walls had what’s known as knock-down texture. This look was achieved by spraying joint compound on the wall, waiting about fifteen minutes for it to dry a bit, and giving it a once over with a straight edge to knock down and flatten the peaks. It was a popular style in the early 1990s when, if the glass blocks that compose the shower in our master bath are any indication, I assume our home was last remodeled. I do not like knock-down texture. My wife does not like knock-down texture. And if I do everything right, my daughter will never know knock-down texture.

Removing this abomination is next to impossible without causing significant wall damage. However, you can cover it up with thin coats of the very joint compound (colloquially called “mud”) used to create the look in the first place. The result, web-based DIYers have promised me, is a smooth wall ready to prime and paint. So, a few weeks ago, I took it upon myself to launch a short, tactical remodeling operation. With a small footprint and exit strategy in place beforehand, I would not be recreating the military errors of the mid-2000s.

I got my first apartment—a one-bedroom place—about a year into the invasion of Iraq. Upon signing the lease, the management company’s representative told me they would redo the kitchen and bathroom countertops before I moved in. A couple of weeks later, I drove a half-full U-Haul to my new front door and unpacked all of my worldly possessions. I placed the microwave on my new countertop, adjusted its position, then decided to put it somewhere else. As I picked it up, I noticed the refinished countertop wasn’t completely dry, and a small gash marked where the microwave had briefly sat. It has bothered me for nearly twenty years.

With my daughter’s birth drawing near, I have made a promise to myself: her nursery will not have a gash.

I set to work figuring out how much of the mud could fit on

the taping knife, how much pressure I should use against the drywall, and how to get rid of the little ridges that seemed

to follow my knife like remoras.

Though not useless, I’m not what most would call a particularly handy person. My mother and father aren’t particularly handy either, so it wasn’t as if I had much chance. When it comes to repairs around the house, then, I start by watching a handful of DIY videos from different people on the same topic. In the case of drywall texturing, I’d hoped one would have a secret texturing technique. In one video, a DIYer suggested mixing water with the joint compound to form a yogurt-like concoction, and then spreading it across the wall with a large taping knife.

I headed to the local big box hardware store for a sackful of powdered joint compound, and a mixer attachment for my drill. Back at home, I dumped some of the floury compound into a bucket and added enough water to create the velvety smoothness of the Yoplait of my youth. I set to work figuring out how much of the mud could fit on the taping knife, how much pressure I should use against the drywall, and how to get rid of the little ridges that seemed to follow my knife like remoras. I did this with a bit of apprehension. I was, after all, destroying something only to remake it better. In theory, it’s called creative destruction. In practice, it’s a crapshoot. After about forty-five minutes, I reached into the bucket and discovered that my “yogurt” mixture had become as pliable as risen dough. It was an unusable mess, and I was inadvertently caught in a quagmire of DIY.

~

Home improvement isn’t just an American phenomenon. The year Moby Dick was published, The Useful Arts Employed in the Construction of Dwelling Houses appeared in the U.K. and gave one of the earliest accounts of why we spend any time fixing up our homes.

As men rise above the rude condition of uncivilized nations, they are not satisfied with the mere [necessities] of life… [The walls of a home] must be covered not only with plaster, but with an ornamental covering of paper or paint. Hence arises occupation for many artisans whose sole business is to make the dwelling agreeable to the eye, after the more necessary and indispensable parts of the structure have been finished.

Until the early 1900s, plaster—a gypsum or lime-based product—was the aspirational material in the U.S. If a homeowner could afford it, their hired artisan made their home’s walls smooth and ready for paint or wallpaper. Few, though, could afford it. However, on the eve of the first World War, a new product came around and was marketed as “the poor man’s answer to plaster.” It was called drywall. Although it wasn’t an immediate hit, the new technology became more refined and increasingly accessible to a legion of homeowners in a quickly growing country.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the annual number of homes constructed in the U.S. remained flat, never reaching above five million. That number doubled during the Dwight Eisenhower administration and remained relatively high for the next few decades. In the vast majority of these homes, drywall cost a small fraction of what plaster had decades earlier. By the time Ronald Reagan took office, many Americans were living in homes that were at least twenty years old. How many needed updates and repairs? Baby boomers were having children. How many of their homes, like mine, needed nurseries?

In 1978, four guys hatched an idea for a giant home-improvement store. Taking advantage of economies of scale, they planned to offer customers lower prices and more choices. In their big boxes—a relatively new retail concept at the time—you would find nearly everything you needed to build your own home (e.g., lumber and drywall), fix up the one you already had, or reinvent a room. The following year, they opened two locations both in suburban Atlanta. In 1981, four months after I was born, their concept, The Home Depot, went public on the NASDAQ exchange. It received less than a paragraph’s attention from The New York Times. By the end of the 1980s, it was the largest home-improvement chain in the country.

Seven kinds of texture can be put on drywall, and I wanted exactly none of them. I wanted a flat wall, but more than that, I wanted the internet to tell me how I had managed to screw this up and turn my compound into a hard, useless mess. A few clicks later, I discovered my error. Joint compound comes in two varieties. Powdered joint compound was designed to dry within an hour whereas the wet version, sold in thirty-pound containers, would stay workable for many hours if not days.

~

When I returned from the hardware store for the second time, I slopped some of the mud into a new bucket, added enough water to reach yogurt consistency, and began anew. Before I started this project, I had absolutely no experience working with wall textures. In the various places I’d lived, I accepted the walls that were given to me. And, if I am to be honest, until I was a homeowner, redoing a wall wasn’t possible. But being a homeowner encourages one to do outrageous things like messing with joint compound and having children. Though I was inexperienced, I had managed to make it to my fourth decade on this planet relatively well-adjusted and interested in a challenge.

In the matter of drywall, I began to learn in a way a child learns. I experimented. I tried new approaches; some were better and others not so much. All the while, I imagined how wonderful the room would look and how this might be the quietest it would ever be.

A couple of hours later, I removed my earbuds, stepped back, and gazed at my work. I was horrified. It looked worse than the knock-down texture I started with I hadn’t only failed myself, I had failed my daughter. What kind of start in life was that?

I heard my wife come up the stairs, so I darted into the hallway to meet her.

“It’s drying,” I said and casually closed the door behind me.

Her eyes, of course, narrowed. But, as she is my wife and the house was not on fire, she allowed whatever was happening in the nursery to continue undisturbed. My pride was on the line.

home improvement…is the impulse to mark that we

were once there, to call a place home.

After the first coat had dried, I stepped back into the room and began again. It took two more coats of mud before the wall saw a crude imitation of craftsmanship honed by plaster artisans portrayed in The Useful Arts. I imagined a drywaller inspecting my work, and summarily laughing off any sort of apprenticeship.

This year, Americans will spend about $4,000 repairing or updating their dwellings. So far, I have spent about $300 on paint, brushes, a taping knife, and the right kind and the wrong kind of joint compound. That’s for one room, and I’m not even finished.

Even when there were no nations and humans lived in caves, somehow we still found time to paint the walls. Maybe, then, home improvement isn’t so much about “rising above the uncivilized”—with all the racist and colonialist notes imbued therein—as it is the impulse to mark that we were once there, to call a place home. A nursery, I discovered, is where it begins.

My daughter can’t know this yet, but she is about to undertake her own renovation: me. No big box store or joint compound needed. Her mere presence in my life, after forty-one years of being childless, is enough to jumpstart a process of creative destruction for which neither of us is entirely ready.

There will come a time when she will be old enough to examine the walls of her former nursery. She will undoubtedly see the unevenness, the shadows cast by the light caressing tiny ridges when the morning sun slips through the branches of our neighbor’s dying holly. If she asks why the walls aren’t smooth, I’ll tell her the truth: we hired a local, unskilled artisan who ran off before the job was done. Eventually, if she’s anything like her mom, I’ll have to explain further: I am a poor man, and this is my plaster wall.

~~~

__________

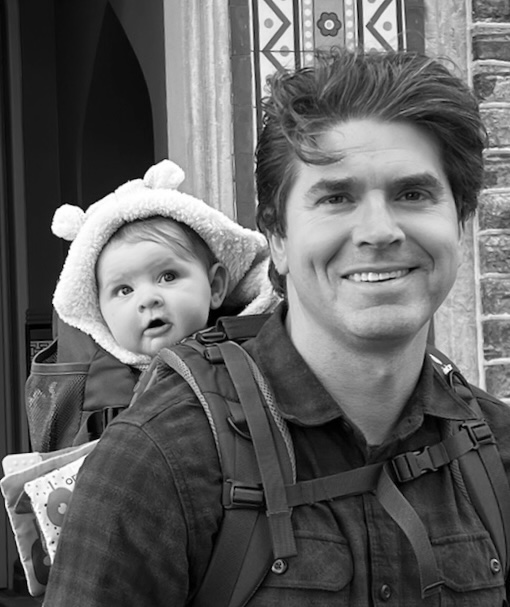

Michael Ward’s work has appeared most recently in X-R-A-Y, Pinch, and The Twin Bill. He lives in Dallas with his wife and daughter.