A Review of Abbey Kiefer’s Certain Shelter

Abbie Kiefer’s debut Certain Shelter (June Road Press, October 2024) opens with “In Praise of Minor,” a list poem that underscores the beauty in things we deem unimportant or avoid out of discomfort. “In Praise of Minor” ends on minor league baseball: “The sky is burdening; / they’re tarping the field. Still, we could stay. / Maybe minor weather. Showers passing by.” We read those last lines and recognize that the choice to stay or not stay is actually about something much more complicated than a spectator sport. The poem sets the tone for the entire collection: finding beauty in spite of—and sometimes even because of—all things minor.

And indeed, at its core, Certain Shelter is about a feeling that is minor (think: melancholy, subdued), to say the least: the speaker is recovering from the death of her mother as she mothers her own children. In addition to this narrative thread, Kiefer explores a diversity of topics, all colored by this grief. There’s a series of poems inspired by classic popular TV shows. There’s a series of prose poems in which all the titles begin with “A Brief History of…” Their subjects range from the abstract (“getting by”) to the hyper-specific (Tarceva, a lung cancer medication). One of my favorite textures of the book comes from learning about the late 19th-and early 20th-century poet E.A. Robinson, who is from Maine just like the speaker and the author. An old mill town provides a fitting emotional landscape for grief: countless closed business—some buildings repurposed, some abandoned altogether. There’s a lived-in quality to the book that seems to say: This is life—not perfect, but full.

Kiefer’s voice and subject matter embody a plain-spoken but hard-hitting Northeastern sensibility, occasionally reminiscent of two great poets who also lived and wrote on the eastern seaboard: Jane Kenyon and Linda Pastan. There are images of gardens with ripe tomatoes, descriptions of how the weather affects you while out running errands, portraits of the female body in senescence—whether from illness or age. What might begin as wading into a “quiet” poem will eventually submerge you in existential waters: “The conductor calling out the name of each station, each / village. So you always knew where you were. How far you / were from home.” At the end of the day, isn’t grief the ultimate homesickness?

Where Kiefer’s poetry derives its ultimate power is the depth of her observations, how she allows the images to speak for themselves. When you’re grieving, every image becomes grief-laden. Kiefer understands this, translating neutral everyday phrases into lines that, in this new lived reality of grief, now signify death and loss. In “Revitalization Efforts: Levine’s Clothing,” the speaker is out to dinner with her two sisters after their mother has died. The poem closes with a description of the waitress: “Shannon / hands us our menus. She’ll be taking care of us.” It’s a folksy phrase we’ve all heard from a restaurant server, but in this context, it is made new, emphasizing who is not there to take care of them. The absence is loud and affecting.

Some of the strongest poems in this book are actually the poems about joy. When you think about the rule of contrast, this makes perfect sense. Like complementary colors, a background of grief allows the joy-forward poems to shine. “I’m So Very Tired,” one of the stand-out poems from the collection, is essentially a catalog of the “generous pleasures” in the speaker’s life. The joy is evident from the content itself, but also from the lyricism within the poem, the abundant assonance and consonance in lines like: “My yard is popular with turkeys. / They’re gawky rockets when they run—” Kiefer is having fun with language here, and so the poem itself becomes a “generous pleasure” for the reader.

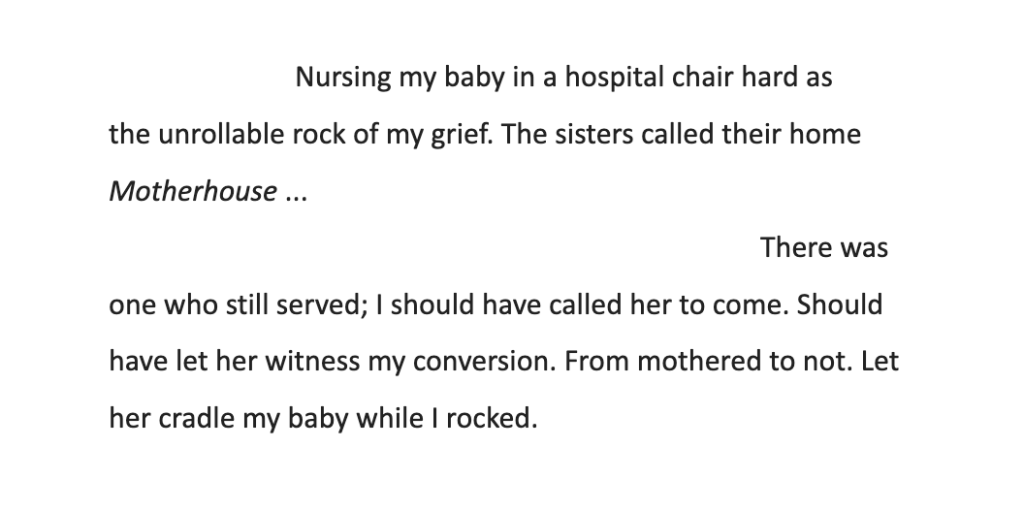

While we encounter many poems that portray the mother as sick or already gone, it’s rare that we get to see the mother when she is vibrant and alive. The mother is clearly beloved, and I would have liked to see with even more clarity just exactly who it is the speaker has lost. The addition of two or three more poems with a focus on the mother when she was healthy would have made an already strong book even stronger. Though perhaps you could argue that the absence is intentional, since ultimately, this is a book about the after. And grief’s devastation certainly comes through. Here is one of the most potent examples, excerpted from the prose poem “A Brief History of the Sisters of Mercy in Portland, Maine:”

It’s the slant rhyme of “not” and “rocked” that lands with such emotional acuity. The circle of life: grieving your mother, mothering your baby. This is the heart of poetry, and Abbie Kiefer gets it. How these two all-consuming experiences almost rhyme, but not quite.

Mary Ardery was born and raised in Bloomington, IN. Her work appears in Beloit Poetry Journal, Best New Poets 2021, Poet Lore, Prairie Schooner, Fairy Tale Review, Missouri Review’s “Poem of the Week,” and elsewhere. She earned a BA from DePauw University and an MFA from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, where she won an Academy of American Poets Prize. You can visit her at maryardery.com.