After “Statesboro Blues”

Pick the blackest night you can. Pull your busted car onto the highway, jeweled with light. Crank its tired speakers as loud as they will go: not nearly loud enough. Don’t run the heat, or you won’t hear. Let the song warm you instead.

Listen. Duane’s guitar cuts through the roar of the crowd like fire through the sky. At the first red light, the bluesy rasp of Gregg’s voice parts the guitar, the drums, like a swimmer’s arms through water: “Wake up mama, turn your lamp down low…” Watch the tailpipe fumes like flags in the wind; brake lights splintered in the windshield like the edges of broken boards. Let the cold seep through the windows, curl its fingers at your shoulders: a ghost, a gentle reminder.

Listen. On the speaker, a dead man sings another dead man’s song. Blues by Gregg, after Blind Willie McTell—brother voices, bound together by their Southern drawls. Gregg was Grandpa’s favorite: spirits kindred as old shoes. Gregg and Willie go like him, strokes and cancers, betrayed by their bodies. Duane wrecks his motorcycle at the intersection of Hillcrest and Bartlett, no older than you, in this car, on this road, this song in your ears. Over a million people die in car accidents each year. Cancer takes another ten. Stroke another thirteen. Wonder at such large men becoming so small, so fragile. Another reminder.

Listen. Remember Grandpa, another car, another highway, in the faded summer of the past: he learns that the Allmans are playing behind him and turns right around—cuts across the grassy median, into the opposite lane, hightails it to the Fillmore to hear this very song played. Remember this and drive through the night—through Thompson, past Milledgeville, where Willie came and went. To Macon, two more hours down the road, to the Big House—the Allman Brothers’ home-turned-studio-turned-museum. For all the times he saw them, Grandpa never made it here. Think of him as you walk the halls of his idols, past worn-out drum kits, yellowed notepads: dormant tools, still warm as struck iron. The guitar that guided you here—the modified Fender Telecaster—hangs behind a sheen of glass, its wood still smudged with fingerprints. Beside it, a picture: a crowded room, arms reaching, the guitar firm in Duane’s hands—the Fillmore East, March 13th, 1971. This date will be your birthday, twenty-eight years later. Marvel at this, the subtle structure of the universe, the harmony of lives like struck chords. Search for Grandpa’s body in the picture, his voice in the crowd. Find him. Be sure of it.

In the future, remember this every time you hear the song. Hear it often.

Listen: this is legacy. Dead men, alive in you again.

Listen: this is all you are.

~~~

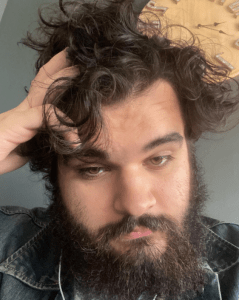

Vasilios Moschouris is a gay stay-at-home writer and Best of the Net nominee from the mountains of North Carolina. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Hobart, Chautauqua Magazine, and on (mac)ro(mic).org. Unfortunately, he can be found on Twitter @burnmyaccountv